TL;DR

In Part I, I explained why I deleted my users table and how I migrated to a third-party authentication provider (Clerk). I introduced a JavaScript array (the cache) that holds the users in the microservice. I have a cron job that runs every 10 minutes and synchronizes the cache with the users in Clerk’s database. This cache array is not naive and is optimized by leveraging heuristics to efficiently query a user by id.

Table of Contents

Open Table of Contents

The Problem

In the previous article, I explained how I migrated to a third-party authentication provider (Clerk) and made Clerk’s user database a part of my application’s knowledge base. Yet, we cannot issue a network request whenever we want to access a user’s information. We need to cache the users in our application in an efficient and scalable way. In this article, I explain a pretty nuanced approach, but it will offer us a O(1) query for finding a user by id, which is faster than JavaScript’s built-in .find(...) with its time complexity of O(n). I also explain the math behind the implementation and the tradeoffs that come with it.

The Solution

Let’s assume we want the cache to be a JavaScript array for convenience. We update this cache in a routine called synchronizeClerkUsers by issuing a “getAll” request to Clerk’s corresponding endpoint every 10 minutes. The response object is an array of users:

@Cron(CronExpression.EVERY_10_MINUTES)

synchronizeClerkUsers(nUsers?: number) {

try {

if (!Number.isInteger(nUsers)) {

// if triggered by cron job

this.clerk.users.getCount().then((nUsers) => {

this.synchronizeClerkUsers(nUsers);

});

return;

}

this.clerk.users

.getUserList({

limit: nUsers,

})

.then((clerkUsersFromApi) => {

this.setClerkUsers(clerkUsersFromApi);

});

} catch {

// Network fetch failed. we keep the old cache and do nothing.

}

}This code block is pretty straightforward. We get the number of users in Clerk’s database and then fetch all of them. We then update the cache with the response. The setClerkUsers method is where the cache is updated:

private async setClerkUsers(newValue: ClerkUser[] = []) {

// Empty the cache

this.cachedClerkUsers = Array<ClerkUser>(this.cacheRange);

// Insert the new values

for (const clerkUser of newValue) {

this.insertClerkUserToCache(clerkUser);

}

}We empty the cache and then insert the new values. The insertClerkUserToCache method is the tricky part where the heuristics come into play. Let’s take a look at it:

private insertClerkUserToCache(user: ClerkUser) {

let index = this.hashToInteger(user.id);

let nTries = 0;

while (nTries < this.cacheRange) {

if (!this.cachedClerkUsers[index]) {

this.cachedClerkUsers[index] = user;

return;

}

index = (index + 1) % this.cacheRange;

nTries += 1;

}

throw new RpcException('Cache is full!');

}First, we hash the user’s id (: string) to an integer within the range this.cacheRange. This is done by the hashToInteger method:

private hashToInteger(str: string) {

const hash = crypto.createHash('md5').update(str).digest('hex');

const num = parseInt(hash, 16);

return num % this.cacheRange;

}This method hashes the string to a hexadecimal number and then converts it to an integer. The integer is then modded by this.cacheRange to ensure the result is within the range. The method is deterministic, and this will later come in handy. The resulting integer will be used as the user’s index in the cache array.

If the cache array at the index is empty, we insert the user at that index. If not, we increment the index by 1, go to the head of the array if we are at the end, and try again. We do this until we find an empty index. If we cannot find an empty index after this.cacheRange tries, we throw an error. This should never happen because we regularly set this.cacheRange to be greater than the number of users in Clerk’s database.

But what is this this.cacheRange property, and where does it come from? To understand it, we take a look at how we implemented the findUserById method:

private async findClerkUserById(id: string) {

const startingIndex = this.hashToInteger(id);

let index = startingIndex;

let nTries = 0;

while (nTries < this.nMaxLookups) {

const user = this.cachedClerkUsers[index];

if (user && user.id === id) {

return user;

}

index = (index + 1) % this.cacheRange;

nTries += 1;

}

const networkLookup = await this.clerk.users.getUser(id);

if (networkLookup) {

this.insertClerkUserToCache(networkLookup);

}

return networkLookup;

}We hash the id to an integer and then use it as the starting index. We then try to find the user at that index. If we cannot find the user, we increment the index by 1 and do this lookup at max this.nMaxLookups times. If we still cannot find the user, we issue a network request to Clerk’s API and insert the user into the cache if it exists. We then return the user if it is found or undefined if it does not.

The Math

For the microservice to work, we need to configure two things: the nUsersToCacheRangeRatio and loseHopeProbability. These are then used to calculate the properties cacheRange and nMaxLookups:

cacheRange calculation:

We know the value of nUsersToCacheRangeRatio since the microservice expects it as configuration, and we get the nUsers information from Clerk’s API; thus we have the value of cacheRange. □

For example, if we have 34 users in Clerk’s database and set

nUsersToCacheRangeRatioto 0.1, the cache range will be 340.

nMaxLookups calculation:

Assuming that the hasher function from users’ ids to integers is evenly distributed on the range [0, cacheRange), the probability of an index being already full is nUsers/cacheRange. This is also the probability of a hash clash:

So, the probability of failing to find an empty index nMaxLookups times is:

If this probability occurs, we give up finding the user in the cache. The calculation of nMaxLookups is then:

Since both loseHopeProbability and nUsersToCacheRangeRatio are configuration parameters, we can calculate nMaxLookups and use it in our microservice. □

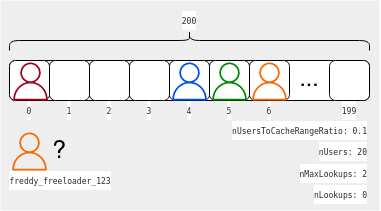

To give a concrete example, assume that we have 20 users in Clerk’s database. We set nUsersToCacheRangeRatio to 0.1 and loseHopeProbability to 0.01. Then, we have:

Assume that we want to get the user with id freddy_freeloader_123 in the scenario described below.

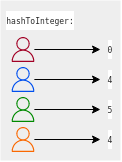

We use the hashToInteger method to get the starting index:

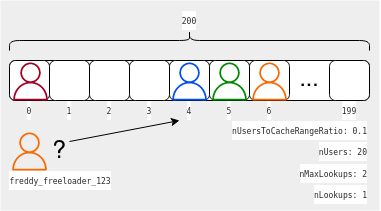

We then try to find the user at index 4.

We see that this index is already reserved for user stella_by_starlight_789 shown as the blue user in the figure. The probability of this is 10% (nUsersToCacheRangeRatio). So, we try the next index, which is 5.

We see that this index is also reserved for another user john_mclaughlin_456 shown as the green user in the figure. The probability of this is also 10%. The probability of both of them being full is then 1% (10% ⋅ 10%). If it is also reserved, we already reached nMaxLookups. We give up, since during the insertion iterations, the probability of such a hash clash was similar, and 0.01% is such a low probability by definition that we can assume that it never happened. We then issue a network request to Clerk’s API as a last resort.

Tradeoffs

If we choose the nUsersToCacheRangeRatio to be too low, we will have a large cache array. This will lead to fewer look-ups for queries but increase the memory usage of our microservice. If we choose it to be too high, we will have a small cache array. This will increase the number of look-ups and result in slower queries. The same tradeoff applies to loseHopeProbability. If we choose it to be too low, we will send fewer network requests but have more look-ups. If we decide it to be too high, we will send more network requests but have fewer look-ups. So, these two parameters should be fine-tuned according to the application’s needs and resources.

Another tradeoff that one might think of is that a malicious user can try to make the microservice send an excessive amount of network requests by sending many requests to the microservice with non-existent user ids. But this is an attack vector we didn’t introduce with this implementation. Yet, to mitigate this, a cooldown mechanism can be implemented to ensure a cooldown period between two network requests to Clerk’s API.

Conclusion

In this article, I explained how I implemented a caching strategy for the users of my application. I introduced a JavaScript array (the cache) that holds the users in the microservice. I have a cron job that runs every 10 minutes and synchronizes the cache with the users in Clerk’s database. This cache array is not naive and is optimized by leveraging heuristics to efficiently query a user by id. I also explained the math behind the implementation and the tradeoffs that come with it. I hope you enjoyed reading this article. As you might have also realized, the math has some flaws, and the whole concept can be improved. As much as I would love to hear your thoughts, I am too lazy to implement commenting and discussion support in this blog, so please tell me your thoughts as a response to my tweet. Until next time, happy coding!